NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory has recently released this map showing global wind energy potential. I didn't realize how much of a difference there was between summer and winter winds.

Looking quickly, it appears that the best sites in terms of sustained yearly wind speeds are: off the coast of Northern California, around Australia and New Zealand, Southern Chile, Somalia, Southern Vietnam, and the Caribbean.

How does this affect birds? Well I think that's still kind of up in the air. Offshore (in federal waters, more than 3 miles from land) wind development would avoid many of the problems usually attributed to migrating birds (especially raptors, which don't migrate over water at all), but could still pose problems for birds that do migrate or travel well offshore.

Here is a satellite tracking map showing a Black-Footed Albatross meandering off the coast of Northern California, one of the areas I mentioned above as having sustained yearly wind speeds and a possible area for deepwater wind farms:

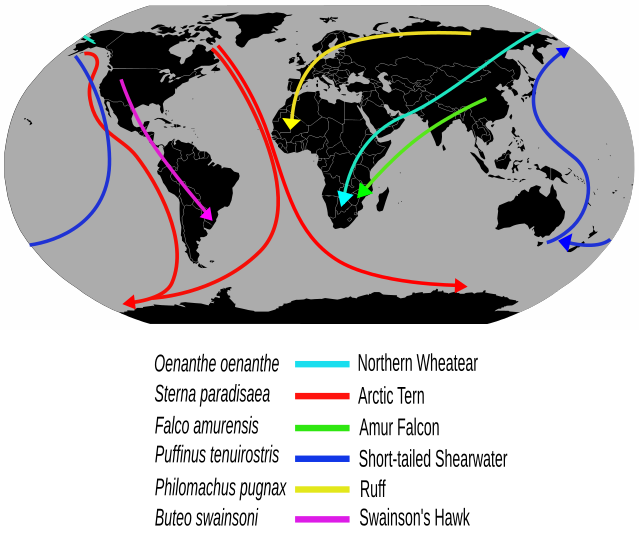

Similarly, some of the migrations shown on this Alaskan USGS site - a really fantastic website - show Brant and Red-Throated Loons migrating well off the coast of California, likewise for Short-Tailed Shearwater and Arctic Terns on the map below (not sure how precise it is).

How would deepwater offshore wind farms affect seabirds? No idea. The only study I know of focuses on wintering Common Eiders. The birds were lured through the turbines using decoys set deeper and deeper into the farm. The fact that these birds were overwintering is important, I think, because their flight patterns are different than birds that are migrating (like the Brant) or foraging (like the Albatross).

For example, most birds - except raptors - migrate at night. Though it is likely that nocturnal migrants fly high enough to avoid rotating blades, lights placed atop turbines for navigational purposes may prove to be a much bigger problem ("In the Gulf of Mexico, a 2005 showed that 300,000 birds die in collisions with pipes and wires each year"). Technological developments in lighting may help.

Birds that feed at sea, storm-petrels, albatross, shearwaters, etc., may also be at risk of hitting turbines. These birds don't generally fly at night, but birds on the lookout for food are not on the lookout for structures. This reasoning has been used to help explain the large numbers of raptor mortality from the Altamont Pass wind farm. It's unclear if there will be a similar effect among seabirds (most sea foragers rely on their noses rather their their eyes), but the topic certainly needs to be studied.

The effects of offshore turbines on seabirds - and maybe more importantly on marine mammals, who may be seriously affected by increased underwater noise and vibration - needs to continue to be explored. I still believe that large offshore wind farms will, in the long run, be easily more environmentally sound than our current sources of electricity, but finding sites that minimize impacts while maximizing energy is key.

2 comments:

Nick, this is a good summary of the issues with offshore wind developments. I think that the F&WS developed guidelines for communications towers (probably working with ABC). I would hope that those would be applied in the cases of wind turbines, too.

Well done! The only study that I know of with off shore wind was in Denmark. However that study was not done at night or under foggy and rainy conditions and was paid for by the wind company. We need independent studies. It seems that mitigation is being relied on too heavily... the Altamont wind farm has shown, so far, that mitigation is just not possible when a wind farm is placed in a location of heavy bird use. The contentious wind farm proposed for Cape Cod would be smack in the middle of a migratory route and endangered species habitat.

Post a Comment